Social Housing History: The Victorian Age

The early history of social housing in Britain

Introduction

There are very few examples of social housing in Britain before the 1850s. Before , any housing built for “the workers” would usually be tied cottages for farm workers or for mill/factory workers. Some of this housing would be cheaply constructed and simply a means to an end to house the workers locally so that the industrialists could make more profits. The coming of the Victorian age brought a new perspective to the mix and the welfare of the workers became important. Healthy workers were good workers, and that in turn meant sustained profits. Arguably, the most famous of the early philanthropists was Titus Salt who started building Saltaire near Bradford in 1853. Two other famous model towns; Bourneville (by Cadbury’s the chocolate makers) and Port Sunlight (by soap makers Lever Brothers), were not started until the 1890s, indicating how advanced Titus Salt’s actions were. In London, William Cubitt (brother of the more famous Thomas) funded the development of Cubitt Town on the Isle of Dogs in the 1840s and 50s but this was more a commercial venture than a philanthropic one. Philanthropists were few and far between and the workers were pouring into the towns and cities and needed a roof over their head. Who was to help them?

In London, the shortage of cheap affordable housing started to become acute in the 1870s as mass influx from the depressed farming industry caused a population explosion. Housing was available, but was usually overcrowded and expensive to rent. There is much evidence available regarding the problem, with stories of tenants sub-letting rooms and they, in turn, renting out space on their floor (this multiple sub-letting was called rack-renting). Sanitation and cooking facilities would be unchanged from when the house would have been occupied by one family. For many of the main tenants, this sub-letting of rooms was the only way to make ends meet, particularly if you were old or infirm and unable to work. This housing became available as the middle classes moved into the suburbs (Brixton, Hampstead, etc) leaving large houses to be split into tenements that were generally unsuited to being split up because of sanitation issues. Rookeries and slums started to appear in pockets all over London, with Holborn particularly badly affected from the mid 1800s. The more famous slum areas of London’s east-end developed later in the 1800s as immigrants headed for the cheap manufacturing areas just east of the City of London. With revolution across the channel in France the industrialists of London needed to ensure that their workers were not inclined to revolution and have a chance to rent good housing near the factories. The government chose not to get involved at this stage, apart from some misguided and unsuccessful attempts at legislation, but to the rescue came a few wealthy philanthropists, enlightened industrialists and sympathetic developers. Eventually, by 1890, the legislative Housing Acts were effective and the County of London had been created, run by a well-led London County Council (LCC).

To compound the housing shortage between the 1850s and 1890 there was the massive railway boom, with rail lines and stations being built all over the country. Competition was fierce, and stations and massive rail yards were built as close as possible to the industrial centres. London suffered particularly in this period. A peculiarity of London’s trains lines is that no main lines were built across London, apart from the relatively minor Snow Hill tunnel close to St Paul’s Cathedral. The main reason was simply one of finances; the cost of land in London meant that that the termini were built round the edge of the then-developed city. To reduce the cost further the lines, stations and goods yards were deliberately sited on cheap land, which often meant slum areas. London Bridge was the first terminus, and was built on cheap land, with the lines up from Greenwich built on a viaduct to further reduce land costs. When the lines were extended towards Charing Cross they were also on a viaduct following a route deliberately chosen to pass through slum housing and so reduce the compensation the the landowners and leaseholders (but no compensation to tenants). This lack of interest in the tenants – the “workers” – was not effectively dealt with by the legislation at the time. The various Acts of Parliament were well meant but poorly executed.

This was the political and physical environment which the housing needed to develop. The next sections deal with how the Social Housing movement started in Britain, what legislation was in place, and a description of London’s borough of Southwark as an example. Use the menus above to navigate through the story of early Social Housing.

Developing the housing

The need for state-sponsored or funded housing will vary according to the needs of the city or populous, and to the politics prevalent at the time. Socialist governments will prefer the state to provide housing and there are many successful examples of this, particularly either side of WW2. But widespread state housing with little choice for those wanting to escape the confines has been shown to create environments where housing, and subsequently the quality of life, to be poor. The author has visited ex-Eastern Bloc countries where city suburbs seem to contain endless rows of soul-destroying concrete tower blocks. Countries with free market economies prefer the people to have as much choice as possible and have the opportunity to purchase their own homes. This also has its dangers as it creates a property-based economy where those who cannot get on the property ladder get left behind and rely on renting low quality accommodation. Neither is right or wrong, and countries will drift one way or the other over time. What is needed is a balance of social and private housing where everyone is able to live safely in accommodation they can afford. This utopia is very difficult to achieve, but that does not, nor should not, stop enlightened governments and local authorities trying.

In Britain the issue of affordable housing for the workers came to a head from the 1850s when massive industrial expansion created centres of industry that needed workers to live close to the factories. This could only be achieved by the industrialists funding the building of cheap housing. Much of the new housing was cynically built, as cheaply as possible, but was often better than immigrants from the countryside were used to. Some employers and industrialists were more enlightened than others, such as Titus Salt, who built a whole town for his workers, called Saltaire, in Yorkshire. But in larger cities the housing could not be tied to one employer as there were usually many potential employers nearby. This meant local authorities providing affordable housing for the working man, but without any restrictions on where he worked or strict rules on what he should and could not do in that dwelling. In London, the lack of decent working class housing for the masses started to become acute as early as the 1850s. In 1851 Prince Albert sponsored the development of the ideal working-men’s dwelling that became known as “Model Dwellings”. The example 4-tenement property was exhibited at the Great Exhibition and was rebuilt shortly after in Kennington Park, Lambeth, where it still stands today.

Initially the philanthropists, such as American banker George Peabody, were encouraged to provide the housing. In fact, the local authorities did not have the ability or funding to do this themselves. They were responsible for the clearance of slums, on health grounds, but could not build replacement housing themselves. This all changed in 1890 when a good Housing Act came into being that allowed social housing to be built and funded by authorities. This happily coincided with the creation of the London County Council (LCC) in 1889. The LCC, along with the major philanthropists, took up the challenge of building affordable housing for “the masses”, without any restrictions on the occupation of the tenants. All the tenant needed to do was pay the rent regularly and abide by the inevitable few rules, which included a maximum occupation for each tenancy to prevent overcrowding.

Read > The Demographics of London

Did they succeed? What lessons were learned? What lessons have the modern-day authorities forgotten about? And why do they need to learn those lessons again?

This “Victorian” section continues by describing the legislation of the time, brought in to help with the cause of the philanthropists, but with little success in the early days. The section finishes by using London’s Borough of Southwark as an example of the successes and failures in the 1800s. Use the menus above to navigate through the pages.

Early housing legislation

There are two ways for authorities to make people do what they want; make it attractive for them to do so, or force them to do so. The best schemes are where there is an effective combination of the two.

One problem faced by city authorities in the 1800s was to ensure that the workers had sufficient housing, of suitable quality, near their place of work. Before trams and worker’s-trains became widespread no worker commuted, and so their place of employment had to be a short walk away. The working days included Saturdays, hours were long, and low wages did not allow for anything to be spent on travel. Half a worker’s earnings would typically be spent on food and this left less than half for rent. The average semi-skilled worker of the time would be earning 18 shillings a week (90p) and spend up to 9 shillings on food. Ideally you would like to have 1/6d per week for beer (much safer to drink than local water supplies) and other things, which left no more than 7/6d per week for rent. This may get you two small rooms in an old house in London. If you had a large family then things were difficult because food and clothing costs go up. Many children sharing one bed was the norm. If you were not skilled, or did not have regular income, you would inevitably earn less than the ideal minimum and this meant looking for cheaper accommodation, and so the spiral downwards towards living in slums began. It was not just the level of earnings that were a problem, it was also the regularity of them. There was no social security in the 1800s. Dockers, in particular, were poorly and irregularly paid and this partly explains their propensity to strike, even in war time. Without effective unions, the workers were sometimes at the mercy of unscrupulous employers, although London and other larger cities had wider employment opportunities for those with the skills that gave them more opportunities to change employer. Outside the cities employment was much more restricted and a change of employer often meant a change of home town, or an exchange of one factory for a similar one nearby.

What the governments of the day wanted was stability and growth. This meant the populace in regular employment, working hard, behaving well, and helping to take the country ever onwards. The enlightened Victorians wanted the workers to have the opportunity to rent decent housing and be able to better themselves and bring up their children in healthy environments. Not all employers agreed, but the later Victorian ideals included education for all children, a church nearby, and regular employment for the head of the household. Many a working man did improve themselves over time by becoming a skilled worker, foreman, or artisan. Many, however, did not have the skills or ability to do this and were in danger of populating the already-crowded industrial areas and slums. Some authorities tackled the problem of slums by simply demolishing them (or getting the railway developers to do it for them). The tenants were not protected by any laws. Although this brutal approach would inevitably encourage many to try and better themselves whenever they could, the majority ended up moving into nearby slums.

The solution was to tackle the problem from two directions: Eradicate the slums and build new housing that the dispossessed could afford. The various Housing Acts of the 1800s tried to enforce that, but not always successfully. One basic principle of slum clearance through all the legislation is that new “working class” housing had to be built to house the same number of people displaced by any slum clearance, and rents charged were to be compatible with those in that area for the same size and type of accommodation. This applied even when railway companies demolished slums. In addition to slum clearances, philanthropic organisations pro-actively built housing for workers on commercially available land and not just on land where slums had been cleared. This approach assumed that: (i) the displaced wanted to live in tenements in the new blocks; (ii) they would be happy with the strict tenancy rules; and (iii) they could pay their rents regularly. The reality for many was somewhat different because they did not have regular income or many families had to supplement their income by the wives and children doing low-paid work at home such as talking in washing or making boxes, or sub-letting space in their already-crowded dwelling to other tenants. The best philanthropic housing from organisations such as the London County Council and the Peabody Trust came with strict rules such as forbidding sub-letting and the taking in of other people’s washing, and insisting that rents were paid regularly.

To Victorian eyes being poor was your own fault, but if you wanted to work hard, live honestly and abide by the rules, there were people and organisations to help. This also meant that there was always a “under class” of people who could never benefit from these ideals and the housing legislation.

For more details on the legislation of the time and its impact click the link below.

Read > Housing legislation in the 1800s

Southwark in the 1800s

Southwark’s early philanthropic housing

When looking into the history of social housing in cities it can be difficult to track the developments in a way that gives a representative timeline. Fortunately, London’s Borough of Southwark, a large area to the south of London Bridge, is an ideal area that encapsulates all the problems that were being forced upon the housing stock in cities by railway and industrial development.

Southwark was typical of the industrial areas of London, with very old housing and some slums under threat from railway developers, but retaining an industrial base – typically food production, wharfage and engineering. Although it was an ancient borough (hence the name of the area immediately south of London Bridge simply being called Borough), the authorities were a collection of parishes, just outside the jurisdiction of the City of London, with its slum and health issues not always sympathetically dealt with by parish and district authorities. The ancient borough was in the county of Surrey until 1889 when it became part of the new County of London. The various parish and district authorities came together only when the London boroughs were formed in 1899 which created the London Borough of Southwark, that included the industrialised areas of Bermondsey and Rotherhithe.

The papers below cover the housing developments in Southwark before WW1 using funding from enlightened philanthropists such as George Peabody. Housing built in Southwark in this period by the London County Council is covered in the “London County Council” link in the menu above.

Read > London_Housing_Southwark_Philanthropy_Part_1

Read > London_Housing_Southwark_Philanthropy_Part_2

London’s East End

The image many people have of the East End of London in Victorian times is one of being street after street of slum dwellings inhabited by Jack the Rippers, prostitutes, beggars and thieves, all in an environment of filth, smoke and destitution.

Whilst there were many pockets of slums where people tried to desperately survive and feed their family there were many areas where, although far from pleasant, honest people managed to make a living and bring up families. The East End developed into a close-knit community (or, more accurately, communities) where hardships were shared and people fought together against poverty, landlords, bosses and sometimes themselves.

The Booth poverty map of 1900 for the East End clearly shows that the slums were in pockets, with many having relatively well-to-do housing only a street away. The black and dark blue areas are the bad slums.

Even though the Booth map above may indicate the East End was not as deprived as many films and television programs make out, it was still a very dirty, smelly and crowded place with old and sub-standard housing where most people struggled day-to-day to earn a decent living. In such a crowded and competitive environment it is not surprising to find the beginnings of racism creeping in. Immigrants were perceived to be taking housing and jobs, and the Jews were the main target. By 1900 the Jewish immigrants had replaced the Huguenot weavers of the previous two centuries and become the target of some ill-placed press articles. But the Jewish immigrants had not created the slums, although they had displaced gentiles from areas around Whitechapel, as can be seen in the map below when compared with Booth’s map above.

The Jewish community were very much self-organising, with new immigrants from east Europe being looked after by the close-knit Jewish community. Their main trades of tailoring, shoe making, furniture and baking were tightly managed by a few established Jewish families.

All the workers of the East End, whether long-established in the area or a recent immigrants from the surrounding countryside or abroad, needed housing but that housing needed improving and the slums needed removing. From the 1860s the only people building new housing specifically for the working classes were a few philanthropic organisations. Some organisations did not last the course, whilst others were very successful. All the successful ones had a requirement to make a small annual profit on rents to enable further schemes to be built and existing buildings managed. The typical profit was 5% and this became known as “5% philanthropy”. The main organisations were: The East End Dwelling Company; Improved Industrial Dwelling Company; Peabody; and (from 1889) the London County Council. The inclusion of the latter may surprise many readers but the early years of the LCC is marked by programmes of improvement and beneficiary for everyone in London. No history of Victorian social housing is complete without mentioning Octavia Hill.

The philanthropist builders

Octavia Hill

Octavia was a philanthropist, but not a builder. She developed the standard method of managing working-class housing through a combination of astuteness and force of character. She was from a middle-class family and obtained funds from wealthy benefactors and then used the money to purchase existing housing that was usually in bad condition. She installed female managers who interacted with the “lady of the house” to build up a relationship with tenants such that they improved their behaviour and were rewarded with repairs and improvements to the building. Good tenants would be further rewarded with better housing and bad tenants would be evicted. She also arranged to have some new housing built (usually cottages). Octavia Hill’s influence of East End housing is fairly minimal but her legacy of tenant-management is one that needs to be re-learnt by modern authorities. For more information on this redoubtable lady go to: https://octaviahill.org/

The East End Dwelling Company (EEDC)

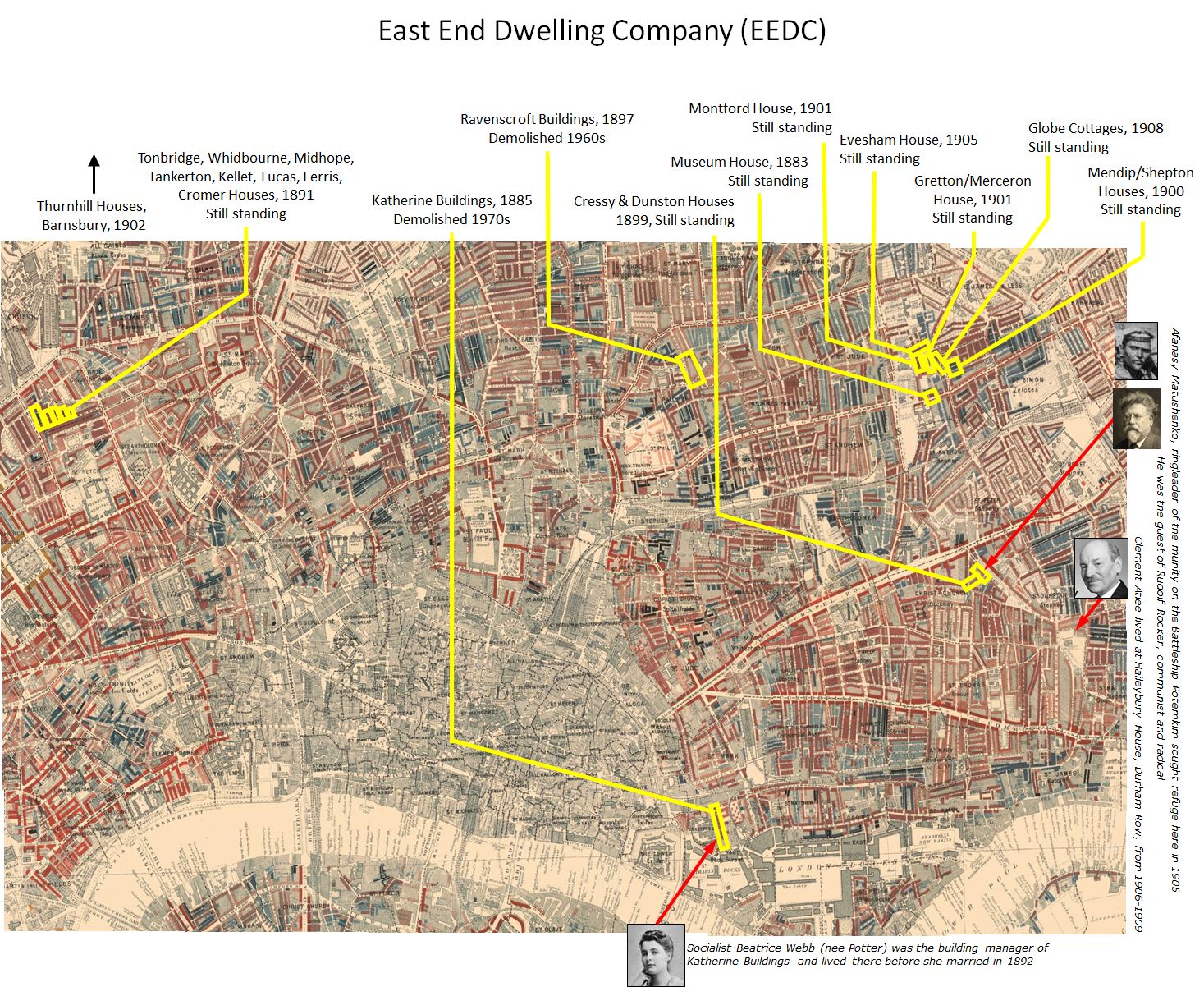

As the name suggests, this organisation operated mainly in the East End of London. They built housing from 1885 until 1906. Below is the Booth map overlaid by the location of the EEDC buildings. The tenants were typically the experienced or mature family men. Many of the buildings still stand – a testament to their quality and the on-going management of them.

Peabody Trust

Peabody is probably the most well-known of all the philanthropic housing developers. The trust built estates of blocks all over London. The map below is the location of those in the East End. The housing was aimed at the slightly better off family man who had regular income.

Improved Industrial Dwelling Company (IIDC)

This rather poorly-named organisation was founded by London printer and one-time Mayor, Sidney Waterlow. His blocks were similar to Peabody’s but generally slightly up-market from them. As a result they were a little dearer to rent than Peabody and attracted the artisan class.

Below is a map showing the location of Peabody and IIDC buildings in the East End.

The London County Council

The county of London was formed in 1889 and the Council dates from then. They took over much of the responsibilities (and staff) of the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW). The leaders were elected and the Progressives (Liberal-aligned) ran the Council until 1907 when the Municipal Reform Party (aligned to the Conservative Party) took over. The LCC built a large amount of housing before WW1, much of it still standing.

The pre-WW1 estates in the map above are described in detail under the “London County Council” section of this website. The largest LCC estate in London was Boundary Street in Bethnal Green.

Overcrowding and racism

One of the most famous areas of the East End is around Flower & Dean Street in Whitechapel. It is highlighted in yellow in the LCC map above.

It’s fame comes from being central to the Jack the Ripper murder stories and myths, and for being the main immigrant Jewish area. It could be considered a ghetto, but that is a negative term and would be doing a considerable injustice to the residents. The Jack the Ripper story is of no concern to this article and is very well covered in many books. What is of interest to this article is the effect the Jewish immigration had on the area, and the claims of overcrowding by press and local politicians.

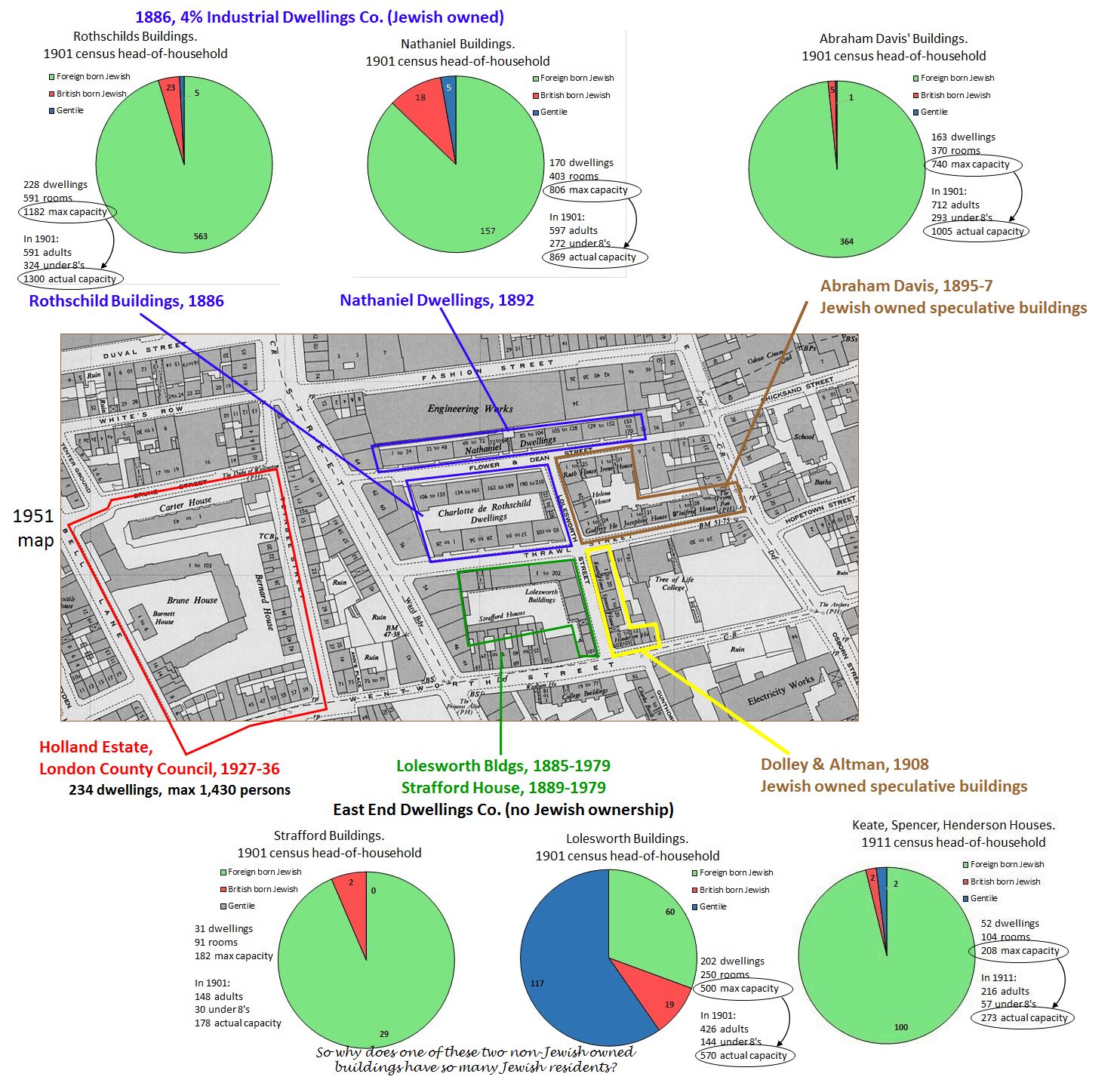

The Flower & Dean Street area consisted of the following buildings:

– 4% Industrial Dwellings Company: Charlotte de Rothschild Buildings, 1887 – 1974

– 4% Industrial Dwellings Company: Nathaniel Buildings, 1892 – 1974

– East End Dwellings Co.: Lolesworth Buildings, 1885-1979

– East End Dwellings Co.: Strafford Buildings, 1889-1979

– Abraham Davis: Helena, Ruth, Irene, Godfrey, Josephine & Winifred Houses, 1897 – ??

– Dolley & Abraham: Keate, Spencer & Henderson Houses, 1908 -??

The 4% Dwelling Company was Jewish owed, and Abraham Davis and Dolley & Abraham were Jewish. The East End Dwellings Company had little Jewish management or control, and nor did the LCC. This would, on the face of it, have the potential to cause problems. But this was not the case. All the housing was managed along similar lines and there was overcrowding in all the buildings and no obvious racial or social tensions between them.

The map below summarises the demographics of the buildings in the Flower & Dean Street area. The post-WW1 LCC Holland Estate has been added for interest. Things to note are the actual capacity (from the census returns) and the theoretical maximum capacity. The latter was calculated at the time by multiplying the number of rooms (bedrooms and living rooms) by 2, giving the adult capacity. The term “adult” was not fixed at the time so I have taken the liberty of basing the term “adult” as any child 8 and above, and therefore taking significant space in a bed.

The trend clearly shows that the Jewish-owned buildings were very predominantly occupied by Jewish people. The surprise is with the non-Jewish owned Strafford and Lolesworth Buildings. Lolesworth has a mix of Jews to gentiles as would be expected, but Strafford is tenanted mainly by Jewish people. The reason lies in what is on the ground floor of the building – shops. The Jewish people occupied all the shops and “lived upstairs”. Note that the 4% Industrial Dwellings Company employed ex-military NCOs as building managers. Rothschilds and Nathaniel were managed by ex-Marine NCOs who were definitely not Jewish. All the buildings, apart from Strafford House, are officially overcrowded and this would have come to the attention of the Borough of Stepney, the LCC and the press.

The racial tension created by the Jewish immigration and blatant overcrowding is best illustrated by press articles and LCC investigations into the tenants of its Boundary Street Estate in Bethnal Green, just a little way to the north of Flower & Dean Street. For more details, go to the paper on that estate elsewhere on this website: <LCC’s Boundary Street Estate>.

This part of London continues to be a centre for immigrants. There is still a strong Jewish presence in the area but subsequent influxes have includes Bengali’s and Somalis. Brick Lane is a very multi-cultural street, and is none the worse for it.

Robin Hood Gardens – still failing to meet the needs of the honest workers?

In the fast eastern edge of London’s East End is Poplar. This area has always been associated with docks and ship building and has been home to many low-paid workers for the last 2 centuries. One small area near the docks known as Wells Street, but now known as Robin Hood Gardens, has always had a reputation for slum housing. The area is now adjacent to the northern portal of the Blackwall Tunnel and also has busy roads on two other sides. The feeling of being isolated is very strong to any visitors today.

The reputation of the area in Victorian times can be seen from this report in the 1880s: “……. Generally the houses were very old and dilapidated, without back yards, and no back ventilation. The ground floor of many of the houses was

sunken below the level of the pavement, and the rooms were exceedingly small. No water was laid on to the existing closets, which were inadequate in number and situate at some distance from the houses to which they belonged. …..” An estimated 1,029 persons were displaced and new dwellings were required to house a minimum of 1,030 people. The freeholder of the land was Sir Edward Colebrooke whose manor was at Ottershaw in Surrey. The clearance of the slums was carried out by the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1884 under the “Wells Street Scheme” and cost London rate-payers £59,119. The site was sold to James Hartnoll for just £5000, but had to be used for the construction of new working-class housing..

James Hartnoll built Grosvenor Buildings in 1886. He was an experienced semi-philanthropic builder of working class blocks in London, but this building was his only unsuccessful one. It consisted of 542 dwellings and a total of 1102 rooms (= theoretical maximum of 2204 persons). 160 at 1-roomed; 204 at 2-roomed; 172 at 3-roomed; and 4 at 4-roomed. Tenements were hard to let initially despite the area being very crowded. In 1911 it was occupied by approximately 1400 adults and 400 children under 8. It had a reputation for being overcrowded, but census returns show it to be no worse than others in London. It seems to have never been managed well as there were rent strikes in 1915, 1939 and early 1960s. In 1911 the building was managed by just one live-in 28 year old clerk to handle 542 families. This clerk/manager had no military background (as was typical in similar buildings). The majority of tenants were of the labouring classes, working in the docks, on ships and in local industry. That, allied to many single-roomed tenements, gave a poor mix that the young clerk was probably unable to handle. The building was purchased by the Greater London Council (LCC’s successor) in 1965 and, despite being structurally sound, demolished and replaced by Robin Hood Gardens. The map below shows the area in 1892 and the picture shows that some of the blocks of Grosvenor Buildings were 6 storeys.

Grosvenor House was replaced by Robin Hood Gardens (1967 – 2017?) and designed by Peter and Alison Smithson as a “city in the sky”. It is one of the more famous London buildings from the Brutalist Movement and was designed 5 years after the similar Park Hill in Sheffield, but without learning from the mistakes, and even adding more. The design also ignored the successful “scissor section” layout advocated and successfully applied at the time to blocks of flats by LCC architect David Gregory Jones. The two blocks consisted of 214 dwellings with all but the ground floor being maisonettes on 2 floors with the rooms split inconveniently between them. The site was surrounded on three sides by busy roads. The walkways only went to the stairs and lifts at each end, not to other levels or the ground, and were too narrow to be “streets” and also too open to the elements. Balconies overlooking the inner grassed space were too narrow to sit on and acted as emergency walk-through fire escapes, so needed to be kept clear. Concrete construction made maintenance and modifications difficult. The slab-sided blocks made the green space in the middle a tranquil place but it was deliberately landscaped (using spoil from the foundations) to prevent it being used as a play park.

The building was never liked by the tenants and this is illustrated by the lifts being vandalised a mere year after the building was opened. Some architects (who have never lived there) wanted the building to be listed by English Heritage, but common sense prevailed and it is due for demolition and replacement by a larger private-social housing development for the wider area of Poplar. Will the residents of Poplar finally get the social housing they want?